| Meat After Meat Joy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

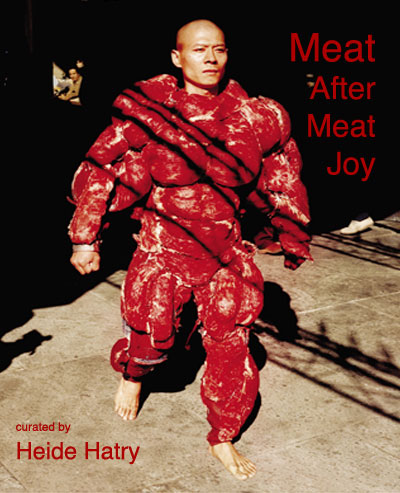

Meat After Meat Joy The following artists were included in the exhibition: Sheffy Bleier (Israel), Lauren Bockow (USA), Adam Brandejs (Canada), Tania Bruguera (Cuba), Nezaket Ekici (Germany/Turkey), Anthony Fischer (USA), Betty Hirst (USA), Zuang Huan (China), Tamara Kostianovsky (Argentina), Simone Racheli (Italy), David Raymond (USA), Dieter Roth (Germany), Carolee Schneemann (USA), Stephen J. Shanabrook (USA), Jana Sterbak (Canada), Jenny Walton (USA), and Pinar Yolacan (Turkey) Interview Christian Holland: In your words, what does "Meat After Meat Joy" mean? Heide Hatry: Carolee Schneeman's Meat Joy performance was among the seminal works of sixties happening and performance art. It consisted of a group of scantily and un-clad people writhing around and interacting among flayed dead animals and animal parts. On the one hand it seemed to be a celebration of life -- it's tone is primarily joyous -- in spite of the fact that life is predicated upon death, and on the other it is an indictment, suggesting that we unwittingly, even ecstatically, embrace the forces of destruction, that of the other and of ourselves. CH: How did you come up with the idea for the show? HH: I have long worked with skin and meat in my own art, and I have compiled a huge file of other artists working with the same media. When I became aware of a couple Boston-area artists who had been creating related work, the painters Anthony Fisher and David Raymond, I drew upon my knowledge to create a collateral group show to amplify the concept and draw attention to the scope of its possibilities. CH: By highlighting meat as a signifier of the "body's" annihilation, do you wish to change the viewers perspective on meat? HH: I grew up on a pig farm. I never really connected this fact to my work until my sister made an off-hand comment a few years ago to the effect of, "so you've finally come home." For me, meat is a primordial fact of life, even if it is a highly problematic one. But I think that my own attraction to meat as a material and a theme is polysemic: I am not so interested in changing any individual's relation to meat as I am in potentiating the tensions in our human relationship to it. To do other than strike an uneasy truce with it is virtually impossible on any significant scale, but to understand -- viscerally -- what is at stake, is deeply important to me. CH: How would "an exhibition on meat be obvious continuation of discussions of contemporary art and the body?" (from Meat After Meat Joy's literature) HH: Well, to begin with, the place of the body, usually the body in some mode of deformation, is crucial in not just contemporary but modern art in general. I want to invoke Bacon and Velicovic among many others, we might even include people like Jenny Saville and John Currin, but it would be easy to fill in an ancestry having done that with the likes of, say, Soutine, Picasso, Duchamp, Ensor, Henry Moore etc. The distorted, damaged, deformed body as depicted in modern and contemporary art is an obvious metaphor for the deformation of the soul, if you will, of the fact that we are all born human and that few of us die terribly human, a sort of Rousseauian perspective. Reducing the body to meat or having humans interact with meat or even avowing the meat-substrate of the living body is a way of addressing the typical deformation of people through any number of social and political processes, not to mention the simpler ones of family, love, rivalry, hatred, etc. CH: By "...After Meat Joy" do you mean: after "Meat Joy?" Is there a feminist subtext to the show? If so, how important was it in choosing the work? Is a feminist reading of meat's status or position in our culture and history needed to better understand meat and its significance? HH: To me it's not absolutely clear to what extent Meat Joy was a specifically "feminist" work. Carolee Schneemann is, to my mind, the first woman artist in history who fully thematized woman's experience in her work, who was fully a woman as she created and who strove to express what that means in every aspect. At the same time, she was and is a deeply humane artist and one of the great political artists of modernity -- both of those facts, not incidentally, have contributed to her "marginalization" if I can say something so seemingly oxymoronic. I do think that Meat Joy rather seems to indict the complicity of women in their own subjection, even while averting to the fact that her liberation is always at hand, immanent as it were, in her capacity for a non-violent, non-contentions, uncompetitive, joyous embrace of the fundamental realities, however distressing, of existence. For me, it's one of her most challenging works, and I wouldn't presume to insist on an interpretation -- I chose it as the starting point, because, like so much else in her opus, it was in fact the starting point for countless other bodies of work by innumerable other artists. I've included other work by female artists in the show which might be seen as seminal (sic), though the historical aspect of the exhibition isn't exactly foremost -- Jana Sterbak's Meat Dress, of which we present a photographic documentation, must be accounted among the crucial feminist works of the era. And any number of things can be said about that, but we counterpoint it with the video documentation of the great contemporary Chinese artist, Zhang Huan 's, stroll through New York in a suit made of meat. The dialogue between these works alone more than justifies the show. As far as the feminist value of meat as a theme is concerned, there's obviously the long-standing view of the female body as "meat" for the predatory male. It does indeed create an intimate perspective on the issues of living and dying, subject and subjected and value and valuelessness for women which men typically cannot approach, and that's deeply involved in the work we're showing and in the work I myself make, but, again, I want to take an oblique, complex and polysemic approach to such questions. There's no perfect perspective on anything and, as in Hegel's Master/Slave dialectic, what we think we know for certain often becomes exactly the opposite of what we thought. For an artist, at least, it's best not to insist on a truth but to hold different perspectives in tension in the hope that a higher truth will emerge, itself to be overcome. Interviewer: Christian Holland has been writing for Big RED & Shiny since its inception, occasionally making movies, herding cats, and dabbling in political consulting. Christian is an executive editor. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||